Trevante Rhodes in one of Calvin Klein’s underwear ads with the men of Moonlight.

Calvin Klein

The sexy Calvin Klein underwear photos of actor Trevante Rhodes that dropped the day after Moonlight’s surprise Oscar win prompted a theater of thirst online. “Let Us Give Thanks to This Image of Trevante Rhodes,” read Jezebel’s reverent headline. “Trevante Rhodes: Hi, how are you? Me: Wet, and yourself?” tweeted one woman. The photos created a real moment in a way that few men’s underwear ad campaigns of this scale have in the recent past, at least since those crotch-grabbing Marky Mark ads of the early ’90s.

If the thirst is real, it is especially so for Rhodes, a former track star, who became the center of attention. He reclines on a leather chair — smiling in one of the pictures, more pensive in another — and is shot from an angle that makes his thighs and crotch the photograph’s protagonists. Arguably, encountering bulging crotches — everywhere from our Instagram feeds to billboards to magazines — has become normalized to the point of cliche; we now think of men’s underwear as inherently erotic. But we forget that these images are also a space where race, masculinity, and sexuality collide in complicated ways.

Underwear ads have always navigated the ambivalence around explicit depictions of the sexualized male body, but they also contend with the erotics of race. The uproar over the first Calvin Klein underwear ad in 1982 was not only about the gay sensibility of its photography, but also about the exoticism of model Tom Hintnaus’s Brazilian-European tanned ethnic in-betweenness. The furor over the 1992 ad campaign featuring Marky Mark grabbing his crotch was a result of his incarnation of black hip-hop gestures through a white, boyish innocence. These latest Calvin Klein images are enticingly revealing — especially the ones making Rhodes a star — but they’re also the result of a trajectory of advertising that delicately dances around America’s fear and desire of black male sexuality, and in that choreography every gesture counts, from a smile to the angle of a bulge.

Fruit of the Loom Christmas ad, 1965.

Fruit of the Loom

Men’s underwear wasn’t always framed through the eroticism of male bodies; pre-1950s ad campaigns were often just illustrations that focused primarily on promoting values like health and comfort, highlighting things like the quality of the wool material or the elasticity of the fit. Critic Richard Martin notes that after World War II there was a shift from health to “happiness ” in marketing campaigns, as underwear was sold directly to consumers — presumably wives and mothers — in store displays rather than through salespeople. “Feel like a million!” proclaimed one 1950 Jockey campaign, featuring an illustration of a man stretching cartoonishly next to a mirror. Tellingly, the models featured in these ads were white, and it wasn’t until the 1960s that black men were incorporated into this happiness, as depicted in a 1965 Fruit of the Loom Christmas ad. But even then, the only representation of black masculinity to appear in the ad, which features multiple generations of smiling white men posing in boxers and almost humorously large briefs, is an innocent black boy grabbing a Christmas ornament as he looks up at an invisible tree. The implication is that only a black boy can fit into this feature, as if an adult black man might appear threatening to the presumed white women buying underwear for their husbands or sons. And so the question of how to evoke the black male body in nonthreatening terms for white consumers recurs throughout the history of men’s underwear.

In the late ’60s, the men’s underwear market was revolutionized with the emergence of “fashion” underwear, a term that referred to smaller bikini briefs and a new panoply of colors. Underwear became a way for men to craft a stylish, urbane, and masculine eroticism on their own terms, in the Playboy style.

The question of how to evoke the black male body in nonthreatening terms for white consumers recurs throughout the history of men’s underwear.

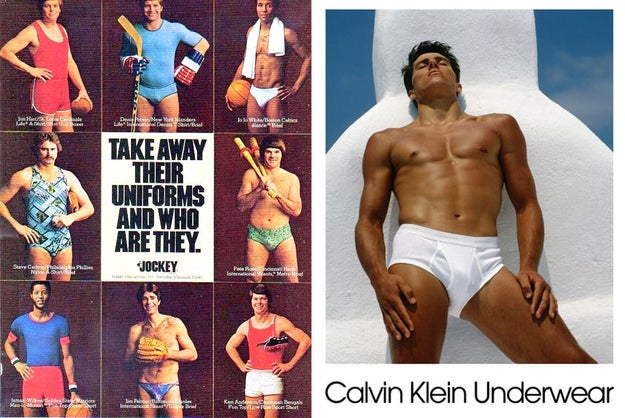

Jockey introduced its version of “fashion” underwear with a series of ads featuring a grid of pictures of celebrity athletes — including football player Ed Marinaro, basketball player Jo Jo White, and baseball player Jim Palmer, alongside the tagline “Take Away Their Uniforms and Who are They.” The photographs display the casual look of amateur portraits taken at Sears; it appears as if the men have been caught in the locker room, their gear still surrounding them as they smile in a wholesome way. Rival brand Fruit of the Loom decided to stay out of the fray and slyly shaded Jockey by telling the New York Times: “The Fruit of the Loom customer is mass America. We’ve not gone after what to us is still a fringe customer. We’re not really after the image of fashion.” But Jockey’s ad campaign purposely chose the ultimate embodiment of innocently straight and rugged Americana in athletes who helped assuage concerns about the effeteness and Europeanness that these new fashions provoked.

The ads also managed to incorporate black masculinity by plucking black bodies from one of the few arenas where they were publicly prized: sports. Even when such black bodies were framed as innocently charming, Ellen Goodman, a white Boston Globe columnist, still “jokingly” wrote about her reaction to seeing a partially nude Jo Jo White in a 1977 column. Of the only black player in the ad campaign, she wrote: “I had just settled into a chair and opened a magazine when who should appear but Jo Jo White, standing half-naked in his little white cotton underpants with a towel wrapped around his neck. … I wish Jo Jo White’s mother would cover the poor boy up.”

This “comic” attempt to turn White into a child by calling for his mom suggests some of the discomfort with the potential eroticism of adult black men. Unsurprisingly, none of the black athletes emerged as the stars of the Jockey campaign. Instead, it was the tanned Orioles pitcher Jim Palmer who became the company’s main celebrity spokesman, a role that made him famous from the mid-’70s until the mid-’80s, when he was shunted aside by the more openly sophisticated and palpably erotic imagery promoted by Calvin Klein.

Left: Jockey ad with Jim Palmer and Jo Jo White. Right: Tom Hintnaus Calvin Klein ad.

Jockey; Calvin Klein

Jockey lost its cultural currency as a purveyor of male eroticism in the early ’80s, when Calvin Klein’s new combinations of race and sexuality pushed the image of “fashion” underwear in new directions. Now called “designer” underwear, the new label was an acknowledgment of the way fashion designers were being considered auteurs and celebrities on their own terms. For the introduction of his underwear line in 1982, Klein hired Bruce Weber — a queer filmmaker and photographer — to shoot the campaign around Tom Hintnaus, a Brazilian-American Olympic pole vaulter whom Klein personally selected. Weber later told journalist Michael Gross that he felt people were “starved for a way to look at men. It was something I had a sensibility about. I knew it was a way for me to start. I took something that was very, very, very easy for me to do in the sense that my feelings about men were very clear to me and I just photographed what I knew.”

Through the now iconic image of a tanned Hintnaus in gleaming white briefs, Weber moved beyond illustrated portraits of middle-class America and uninspired locker room photos. He used the angles and framing of gay pinup magazines; he emphasized Hintnaus’s bulge by shooting him from below, moving away from respectful portrait-like shots that previous campaigns relied on. Both Hintnaus’s flung-out hip and the upward direction of his face suggest a kind of loose ecstasy, though the source of that ecstasy remains tantalizingly unclear, and is part of what made the photograph the object of so much speculation.

The image became a sensation. In 1989, American Photographer magazine selected it as one of 10 photographs that changed America because it signaled, explained curator Diana Edkins, a liberation of male sexuality. Less noted are the image’s racial complexities: Hintnaus became a kind of Brazilian supermodel precursor to Gisele Bündchen. Just like Bündchen, he was of European descent (Czechoslovakian), with the right amount of tanned ethnicity to seem exotic but safe. And this combination of racially exotic imagery — conveyed through Bruce Weber’s coded white gay sensibility — helped Calvin Klein dominate the 1990s and the 2000s.

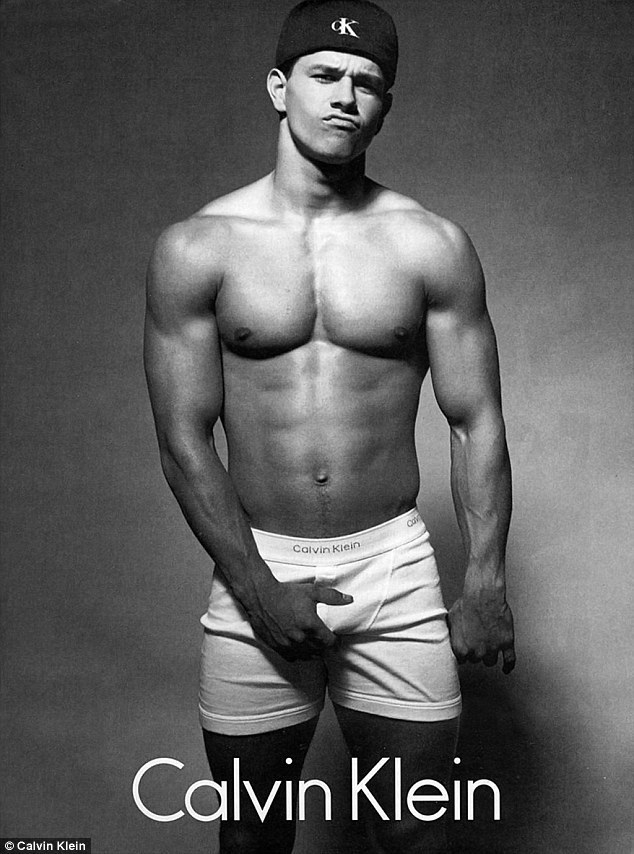

Though Calvin Klein’s ability to exploit the erotics of race in a way that was both mainstream and subtly transgressive continued with its 1992 ad campaign featuring Mark Wahlberg, during the era when he was only known as Marky Mark (and was part of the Funky Bunch). The fashion designer personally selected him after Wahlberg kept dropping his pants to reveal Calvin Klein–branded underwear during his concerts. Wahlberg’s early years — before he turned to acting — are now mostly remembered through the famous photographs taken by Herb Ritts to promote the brand’s boxer briefs.

The ads also managed to incorporate black masculinity by plucking black bodies from one of the few arenas where they were publicly prized: sports.

Ritts famously directed MTV videos for everyone from Madonna to Janet Jackson, and later photographed a queerly gender-bending K.D. Lang and Cindy Crawford Vanity Fair cover. And like Weber, he had a white gay sensibility that glorified the aesthetics of conventional hypermasculinity and emotionally distant subjects. His photos for the 1992 campaign exploit a racialized “good boy” and “bad boy” duality. In one picture Wahlberg smiles innocently, grabbing at the sides of his boxer briefs — evoking the kind of white beefy American college boys that fellow photographer Bruce Weber would later make ubiquitous through his Abercrombie & Fitch campaigns. But the most influential image — still re-created today — is Wahlberg in a backward hat, pouting and grabbing his crotch. He grabs himself in a style and gesture associated with rap and hip-hop cultures and looks aggressively beyond — almost through — the camera. In a way, he is countering his objectification with a look that critic Richard Dyer calls the castrating gaze. And if there were still any questions about his sexuality or masculinity, his manliness is emphasized through images that pair him with the waifish ’90s queen of heroin chic, Kate Moss, who appears topless in simple white Calvin Klein-branded panties.

Mark Wahlberg’s iconic ad.

Calvin Klein

These images didn’t just create massive publicity for both the brand and Wahlberg at the time; they continue to circulate today. They also allowed white performers to momentarily take on the frisson of black masculinity — the desired and feared myths about aggression and hypersexuality — without any of the cultural baggage of surveillance and fear that comes with actual black masculinity. (Wahlberg himself recently sought to scrub his criminal record of a racialized hate crime, showing how his reliance on white innocence wasn’t just a performance.) These suggestively contradictory images have been most recently re-created by young white pop stars — including Justin Bieber and Nick Jonas — in order to make statements about leaving behind the innocence of their early images through a “bad boy” appeal that is coded black: in Bieber’s case, his embrace of the Wahlberg aesthetic led to an actual Calvin Klein contract; Jonas re-created it in a gay magazine cover story to appeal to his gay fanbase for his last album.

In his book Male Impersonators, Mark Simpson argued that unlike Madonna, who was prized for her inauthenticity, Wahlberg’s appeal for gay men was based on his authenticity as straight trade. Yet this was especially the case for white gay men, who could take his problematic co-optation of black masculinity at face value. And because Wahlberg’s image plays with the black and white racial binary that defines the American racial imagination, it continues to resonate more than, say, the Hintnaus image, which gets lost in the in-betweenness of Latinidad. Even Mario Lopez, who is Mexican-American, picked the Wahlberg image instead of Hintnaus’s when he re-created famous poses of sexy men for People magazine’s “Hottest Bachelor” issue in 2008. (Though he opted for the “good boy” version of Mark.)

Yet even as Calvin Klein’s brand exploited both the in-betweenness of Latinidad and the gestures of hip-hop black masculinity on white bodies, it took years to feature an actual black underwear spokesman.

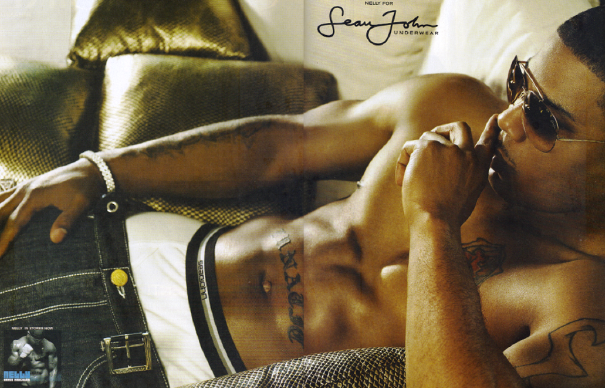

Nelly’s 2008 Sean John ad.

Sean John

When Calvin Klein finally turned to an actual black celebrity as an underwear spokesperson — in 2007, on the 25th anniversary of the underwear line — the brand no longer dominated contemporary culture in the way it once had. It stayed away from any association with hip-hop culture, and in some ways contemporary culture, by picking the Beninese-American actor Djimon Hounsou. Hounsou rose to fame through his representation of a leader of an African slave mutiny in Spielberg’s 1997 historical saga Amistad. It is not an accident that Klein picked an actor seemingly disconnected from contemporary time and space. Apparently, any actor or rapper too explicitly connected to contemporary African-American culture might be too “real” for the brand. (Klein later selected Mehcad Brooks — most famous for his role on the HBO fantasy show True Blood — as part of a 2010 multicultural campaign called “X Marks the Spot.”)

Nelly’s refusal to fully expose his body could be interpreted as less of a whim and more of a political stance against the objectification and sexual exploitation of black male bodies.

Shot by Peter Lindbergh, Hounsou was made to look like a piece of steel — the new underwear line’s name — with the emphasis on his glistening skin and the enhanced tone contrast of the background and his body. Critic Robin Givhan found the images unremarkable, perhaps because by then the campaign’s visual language had become too anachronistic and normalized. The photo in which Hounsou kneels as if he is about to take off running seemed to harken back to the emphasis on black athleticism in the Jockey images, and the second ad, which was shot from below, felt like a re-creation of the Hintnaus pose with the flung-out hip.

At the same time, black fashion houses like Sean Combs’ Sean John were already promoting their own version of men’s underwear under different terms — explicitly representing a hip-hop aesthetic. Sean John picked rapper Nelly to promote its loungewear and underwear line in 2008. In one of the brand’s ads, Nelly appears on what looks like a building rooftop; he slouches on a couch in another. But despite that he’s promoting underwear, Nelly never actually appears without his pants. Instead, he wears oversize jeans, and presumably as a way of avoiding the problem of appearing too aggressive, he wears sunglasses so that he never meets the viewer’s eye. The “chaste” imagery prompted jokey complaints that he wasn’t revealing enough, and some gay websites even went as far as photoshopping him into tight, revealing jockstraps.

But in some ways Nelly’s decision to not show it all was in keeping with the way hip-hop culture deals with the surveillance of black bodies. Critic Imani Perry has noted how the politics of hip-hop dress emphasizes “the abstract, as opposed to the revealed body.” Nelly’s refusal to fully expose his body could be interpreted as less of a whim and more of a political stance against the objectification and sexual exploitation of black male bodies. The photographs suggest that for black men the real transgression might be covering up, not taking it off – refusing the gaze rather than engaging it. And they provide a striking contrast to the popularity — and aesthetic — of the Trevante Rhodes images.